The Trump admin sent him ‘home’ to a land where slavery lives on

Mauritanians in the U.S. fear they’ll share the fate of Issa Sao, who was sent back to a country where thousands of blacks are still enslaved.

Mauritanians in the U.S. fear they’ll share the fate of Issa Sao, who was sent back to a country where thousands of blacks are still enslaved.

Image: Mauritanian anti-slavery protesters

Mauritanian anti-slavery protesters march to demand the liberation of imprisoned abolitionist leader Biram Ould Abeid in Nouakchott on May 26, 2012.Joe Penney / Reuters file

By Lisa Riordan Seville, Adiel Kaplan and Dan De Luce

The agents came for Issa Sao just before midnight.

For nearly five months, the 37-year-old had been moved from one detention center to another, hoping the United States would not send him back to a country that had jailed, tortured and expelled him.

Behind him, in Ohio, lay his family — a wife, stepson and a young daughter who loved to smile big in photographs — and all 14 years of his life in the U.S. In front of him loomed Mauritania, a desert nation in West Africa that still tacitly permits the enslavement of black Mauritanians like Sao.

Late on the night of Oct. 15, Sao’s lawyer, Julie Nemecek, got his panicked call. “His exact words were something like, ‘Oh my God, they are taking us tonight! They are putting us on the charter!'” she recalled. The next day, Sao was gone.

Image: Issa Sao

Issa Sao with his daughter.Courtesy Sao family

The flight that took Sao back across the sea was part of an aggressive but little-noticed piece of President Donald Trump’s immigration crackdown. The administration has redirected hundreds of millions of dollars and shifted diplomatic priorities in its effort to increase removals to countries, most in Africa and Asia, that have previously dragged their feet or refused to accept deportees the U.S. wants to send back.

It’s an unprecedented push to deport a relatively small number of people.

There are an estimated fewer than 120,000 people with deportation orders from the 59 countries ICE has recently labeled “uncooperative” or “at risk of non-compliance” with deportations, according to an NBC News analysis of federal data from 2003 through 2017 kept by Syracuse University. That’s about 1.5 percent of the estimated 11 million unauthorized immigrants living in the country, based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Supporters of the effort say Trump’s unbending approach has forced progress on an issue that had stymied agencies in the past, and is crucial to public safety. But critics assert that this pressure places deportations above diplomacy and could damage U.S. relationships with key allies, including Morocco and Iraq, partners in the fight against terrorism.

For the Mauritanians, advocates and Democratic lawmakers say it’s a question of basic human rights.

In early November, Trump cut off trade benefits to Mauritania for its failure to combat forced labor and “the scourge of hereditary slavery.” Thousands of black Mauritanians like Sao live in slavery — a number that activists say is declining, but that the UN said could be up to 20 percent of the country’s population less than a decade ago.

Yet since Trump took office, the U.S. has deported a record number of people to that very country. The 79 deportations last fiscal year mark a more than 900 percent increase over years prior, according to an NBC News analysis of ICE data.

Sao was among the first to be removed this fiscal year, which began October 1. ICE said 22 Mauritanians are currently in custody and could soon be returned.

“This isn’t just about immigration,” said Nemecek, Sao’s attorney. “It’s our government handing people to their persecutors.”

Image: Issa Sao

Issa Sao with his stepson outside the White House in Washington, DC.Courtesy Sao family

The diplomatic challenge of uncooperative countries has been around for years. Prior administrations tended to view so-called “recalcitrant” countries – nations unwilling to accept deportees — as a relatively minor issue in the wider diplomatic landscape.

But not the Trump administration.

In his first week after taking office, Trump signed an executive order directed at enhancing public safety by cracking down on immigration. Tucked within it was a mandate to diplomats to make accepting deportees a priority in negotiations with foreign countries.

In fiscal year 2017, the number of people deported to countries on the list of recalcitrant nations more than doubled, from 970 to 2040.

Toward the end of the Obama administration, recalcitrant countries became a pet issue of congressional Republicans. Among them was then-Sen. Jeff Sessions, who served as Trump’s attorney general until last week, and his former senior adviser Stephen Miller, who has shaped the president’s hard line on immigration.

Under pressure from legislators, the Obama administration had increased the deportation of immigrants with criminal records and histories of violent crime. There had also been an uptick in deportations of immigrants like Sao, who’d been living in the U.S. without status for years despite orders of deportation.

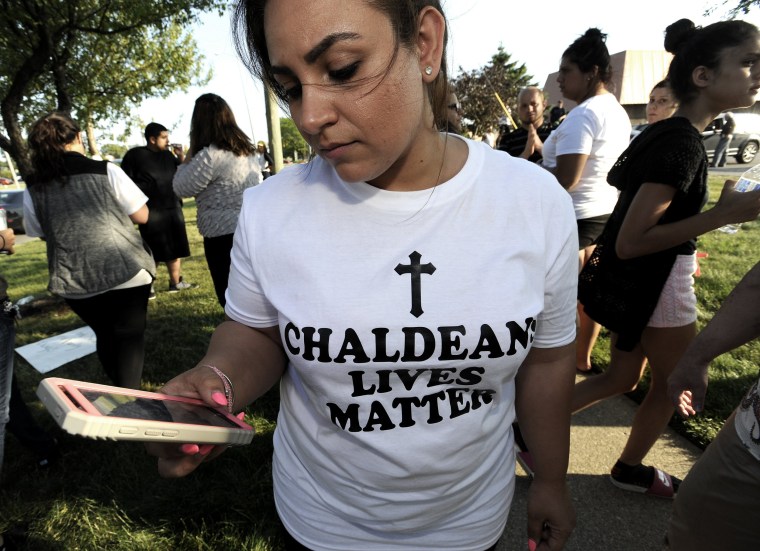

Amal Hana, of Warren, Mich., holds a photo of Donald Trump on June 16, 2017, outside the Patrick V. McNamara Federal Building during a protest in Detroit. Hana joined hundreds others to protest the recent ICE raids in which more than 100 Iraqi nationals in Metro Detroit were detained.

Amal Hana, of Warren, Mich., holds a photo of Donald Trump on June 16, 2017, outside the Patrick V. McNamara Federal Building during a protest in Detroit. Hana joined hundreds others to protest the recent ICE raids in which more than 100 Iraqi nationals in Metro Detroit were detained.Tanya Moutzalias / MLive.com via AP file

When the Trump administration took office, Miller led an effort to zero in on deporting people from nations on ICE’s list of recalcitrant countries, including failed asylum-seekers who had lived in the U.S. with deportation orders for years, two former and one current U.S. official told NBC News.

“[Miller] maintained that it was a law enforcement issue,” said former U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam Ted Osius. “Some thought it was a racist policy, as it targeted African and Asian nations.”

In closed-door negotiations and by levying a record number of visa sanctions, the Trump administration tried to force the deportations through.

As countries that had resisted accepting U.S. deportees for decades quietly began to acquiesce, ICE sweeps became more frequent. Some who were arrested had long criminal records and convictions for violent crimes. Many did not.

Immigrants like Sao, who had no criminal record but had lost his bids for asylum, had always been near the back of the line for deportees. Suddenly, deportation loomed much more likely.

A spokesman for ICE said that while it “continues to prioritize threats to public safety, the agency will not exempt classes or categories of removal aliens from potential enforcement.”

Working in conjunction with the State Department, the Department of Homeland Security has made “tremendous progress,” ICE officials told NBC News, adding that countries are obliged under international law to accept deportees.

As deportations picked up, the list of nations officially deemed “recalcitrant” by ICE shrank from 20 to nine.

“We consider all options at our disposal,” a State Department spokesperson told NBC News, “taking into account complex bilateral relationships, foreign policy priorities, and other extenuating circumstances.”

“In many cases, diplomatic efforts are successful in addressing the problem,” the spokesperson added.

But nations that don’t cooperate are increasingly facing retribution. Since September 2017, DHS has imposed visa sanctions on six countries. Only two countries had ever been sanctioned before over deportations.

That hardline approach has proven effective, said Michele Thoren Bond, a former State Department official, who worked on the issue of recalcitrant countries under Obama.

Recommended

Paradise, California, in ruins as Camp Fire continues to rage

Schiff: Trump fire tweet shows ‘How little he understands the job he has’

“We are seeing real success, probably because countries believe they’ll be sorry if they don’t comply,” said Bond.

But others argue this push to deport could put other diplomatic priorities at risk.

“The administration has not hesitated to bully smaller nations to force compliance with the new policy,” said Osius. “It has been extremely damaging in Laos and Cambodia, where relationships have sunk to new lows.”

More strategically important countries are also in the administration’s crosshairs. Morocco was considered recalcitrant when Trump came into office, and is one of more than a dozen nations that have since come off the list.

From trade to help with counterterrorism and fighting violent extremism, the U.S. has long viewed Morocco as an important partner. Imposing visa sanctions could have jeopardized cooperation on an array of issues, experts said.

“If you want to do business in Africa, you can’t have that conversation without Morocco,” said one former diplomat, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Last summer, word of a shift at ICE started spreading through the tight-knit community of Mauritanians living in Columbus, Ohio.

Most were asylum seekers from the desert country in northwestern Africa driven out in a bloody ethnic conflict that began in 1989, when the ruling minority of Arab Moors expelled some 70,000 non-Arabs.

The purge left thousands of black Mauritanians effectively stateless. Those who now return arrive without citizenship papers. Advocates told NBC News that leaves them vulnerable to enslavement, which despite being officially abolished in 1981, is still pervasive.

“I felt I was free.”

But Mauritanians had long felt safe in the U.S. Even those like Sao who had lost asylum cases were allowed to remain because Mauritania didn’t recognize them as citizens and refused to take them back. DHS had granted them work permits, set up regular check-ins and allowed them to stay.

Savings from jobs on factory lines and at small businesses paid for down payments on houses. They married, settled down, had kids.

After 26 years, limbo came to feel like permanence for Sy, who asked that his first name not be used. Like Sao, he had no criminal record, but had lost his asylum case and faced a standing order for deportation. Once a year, he checked in with ICE, then went at the agency’s bidding to the Mauritanian embassy to request a passport so ICE could deport him. Each time, Mauritania turned him down. He went back to his daily life.

He sold clothes by day, drove Lyft by night and cared for his four children in between, including his disabled son.

“I felt I was free,” he said.

Then came the messages from friends in Columbus and Cincinnati. Mauritanians turned down for a passport just months before learned suddenly that ICE had obtained a temporary travel document — known as a laissez passer — that would allow them to be deported. But they still would not have any proof of citizenship when they landed in the country.

As men like Sao were arrested at ICE check-ins and boarded onto planes, Sy felt his own stability slipping away. He now checks in with ICE every three months. Each time, he tells his children if he doesn’t return to them, it’s because agents dragged him away.

“I ran away from the country 26 years ago. I ran away for my life,” said Sy. “Even now I’m still running.”

Those same worries now pulse through Cambodian households in Modesto, California, and the pews of Iraqi Christian churches in suburban Detroit. Somalis who fear returning to their war-torn country talk of fleeing to Canada. At least one Senegalese mother from Ohio already has.

It’s not only the loss of lives built in the U.S. over decades, they said. It’s also the risk of going somewhere they fled from that may still not be safe.

Some, like Sene Sem, fled genocide as toddlers — or were born in refugee camps — and have no memory of the country the U.S. is pressing to take them back. Sem, who worked at a Rhode Island soap factory until ICE picked him up on Sept. 11, is fighting deportation to Cambodia. He was convicted of assault in 1990 and has a standing order of deportation.

“It would be devastating to us and to him,” said Sem’s wife Sarah Houey, who said her husband barely speaks Khmer, Cambodia’s national language, and would be rootless. “There’s no family. There’s no way he can survive there.”

ICE Rounds Up Iraqi Immigrants in Metro Detroit

June 13, 201701:51

Some of the Iraqis rounded up who were born in refugee camps have not been recognized by the country as citizens. A number are from the minority Chaldean community, Christians who do not speak Arabic in their homes and fear they would face religious persecution if returned.

Last year, communities in Minnesota were shaken when the U.S. flew five charter flights carrying more than 500 Somalis back to their native country, a failed state that the State Department warns is riddled by “crime, terrorism and piracy.” A sixth flight carrying 98 Somalis last December only made it as far as Senegal. Detainees sat chained on the runway in Dakar for 23 hours before the plane few back with only muddled explanations from ICE about “logistical problems.”

The increasing pace of deportations comes with a hefty price tag for taxpayers.

This summer, to foot the bill for skyrocketing detention and removal costs, the Trump administration quietly funneled $202 million toward detention and removals from other budget lines within DHS, including FEMA.

More than half of the increase went to cover a nearly 30 percent overrun for transportations and removals. A key justification was the growing number of special charters ICE was running to once-recalcitrant countries, like the flight that took Issa Sao back to Mauritania last month. A single charter flight can cost more than $600,000, according to declaration from an ICE official from a lawsuit about deportations to Iraq.

Sao had tried for more than 10 years to be granted reprieve in the U.S. ICE officials said courts had “uniformly held” that Sao “did not have a legal basis to remain in the U.S.”

After he was detained, lawyers went to the courts one more time to halt his deportation and reopen his case. Six men they knew who had been deported were imprisoned upon their return to Mauritania. They didn’t want Sao to be the seventh.

A court turned Sao down on Oct. 15. That night, ICE took him away.

After the scramble to confirm that Sao was in fact gone, Ohio waited. His family hoped he would call. Mauritanian activists kept an ear on the whisper network. The group of attorneys and advocates who had rallied around the community worried, including Lynn Tramonte, with the immigrant’s rights group America’s Voice.

The day after the charter plane left an Arizona tarmac with Sao shackled aboard it, his wife got a call that he had landed in Mauritania, Tramonte said. Within a matter of days, she added, fearing for his life, Sao fled Mauritania once again.