Warren-raised DJ in Iraq tweaks IS with Detroit flavor

George Hunter, The Detroit News

George Hunter, The Detroit News

(Photo: Clarence Tabb Jr. / The Detroit News)

Like many morning radio personalities, Noor Matti pokes fun at people in the headlines. But unlike the Detroit disc jockeys he grew up listening to, he knows his on-air antics could get him killed.

Matti, a Chaldean, often uses his time on the air to needle Islamic extremists — a dangerous proposition since his station is in Iraq, less than 50 miles from Mosul, the capital of the Islamic State group, often referred to as IS or ISIS.

Matti’s English-language station, Babylon FM, broadcasts from Erbil in the country’s Kurdistan region, a relatively safe area for Christians, although the threat of an IS attack is always present.

“They’ve caught ISIS members in the city,” Matti said. “There have been ISIS attacks. So it’s something you’re always living with. I know what they do to people, with the torture and beheadings. And I know they’d like to get me.”

The 31-year-old former Warren resident and Wayne State graduate says he isn’t worried about retaliation, since he’s on a mission to offer an alternative to the constant barrage of extremist religious propaganda broadcast by IS radio stations.

“Music is a big middle finger to ISIS,” said Matti, who hosts “The Breakfast Club,” a Detroit-themed show that airs from 8-10 a.m.

“With music, you can talk about love, or whatever else is on your mind, and you can do it free of being threatened. And ISIS hates that. When ISIS invaded Mosul (in June 2014), they took all the musical instruments into the city center and burned them. Every piano; every guitar; every drum set. Every CD.

“That, of course, is the core of their principle: believing people don’t have the right to express themselves. The Islamic State expresses everything for you. So I think we’re bringing hope with our show. A lot of terrible things are happening every day. It’s a difficult job to make people forget about ISIS for a few hours in the morning, but I try.”

Matti patterns his show after “Mojo in the Morning” on 95.5 FM. “We play music, do some pranks, talk about what’s going on. Every once in awhile we’ll talk about serious topics, but we don’t get political. It’s about other things that affect people’s lives besides war and ISIS, because that’s what we’re surrounded by 24/7. People need a break.”

Matti may avoid political topics, but IS is often the recipient of his sardonic “Wahshi (Donkey) of the Day” award.

“We make fun of ISIS,” he said. “They do things that are so serious and so sad; we just try to laugh about it. They got the award just the other day, after it was discovered they’d destroyed the oldest Christian monastery in Iraq (the 1,400-year-old Saint Elijah monastery in Mosul). So, congratulations, ISIS; you’re the Wahshi of the day.

“Our signal reaches them. They hear us. I wouldn’t say I’m scared, although I know the threat is there. I know someone is probably planning to come get me. I don’t think about it. If something’s going to happen, it’s going to happen.”

Parents fear for son

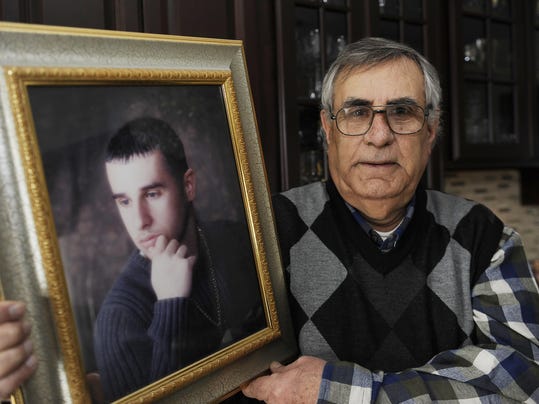

Matti’s parents in Sterling Heights feel differently.

“His mother and me are both afraid for him,” said Fred Matti, a 68-year-old retired teacher. “The area he’s in is so dangerous. ISIS is so close. … He’s our only son, and we want him to be safe.”

The Matti family — 8-year-old Noor, his sister, Solaf, father Fred, and mother Souad — fled Iraq in 1992, after Operation Desert Storm, when Saddam Hussein’s forces bombed their home in the Kurdish region. They settled in Metro Detroit, home to the world’s largest Chaldean population outside the Middle East.

Noor Matti, who was profiled in Bridge magazine recently, says his life changed at age 15, when he first heard Eminem on the radio. He says he tricked his father into buying the “Slim Shady LP” CD, which he couldn’t purchase because of its explicit lyrics.

“I still have the receipt, dated March 21, 1999. I memorized every line in that album. And slowly I got into music, by making fan websites for various artists, and CD mixes via (the file-sharing program) Napster to sell in the streets.”

After graduating from Warren Fitzgerald High School in 2003, Matti enrolled in Wayne State University, where he majored in multimedia.

“But after the first semester ended, my parents told me that wasn’t a real job. Like a lot of immigrant parents, they wanted me to be a doctor. I wasn’t strong enough to stand up to them, so I graduated (in 2008) with a bachelor’s degree in biology.”

Matti says he wandered around for a few months after graduating, unsure of what to do. He’d been accepted into optometry school, but says he didn’t have the heart to enroll.

“I was in that stage after college where you don’t know where your place in the world is,” he said. “I decided to go back to Iraq to visit my cousins.

“What I found was a developing country. Iraq was rebuilding (after Saddam’s regime was toppled), and I wanted to be a part of it. So I called my parents and told them I was staying. They had mixed feelings about it. They didn’t mind it too much until 2014, when ISIS came in.”

Arts to counter extremism

Noor found work as an English teacher. He taught for four years, until he saw that Babylon Media, a multimedia company in the Christian section of Erbil, was launching an English-language radio station.

“It’s what I was meant to do. During the interview, I told (the manager) I was the perfect man for the job.

“I’m part of this movement that’s trying to put liberal arts into the society. We’re countering ISIS, and the (Kurdish) mosques with their preaching. We’re making young teen girls fall in love with Justin Bieber. You have no idea how important that is. If these kids learn the culture, they won’t grow up to be anti-West, or anti-Christian.”

Matti said IS blocks his station’s signal from reaching Mosul. “They opened a station with the same frequency as ours that has nothing on it, except sometimes they’ll broadcast Koranic verses.

“They have multiple radio stations in Iraq that constantly talk about how terrible the West is. We offer an alternative to all that hatred.”

Matti says he doesn’t try to hide his identity when leaving Erbil.

“I just go about living my life, and don’t worry about what might happen. Hopefully, if I do get captured, it’ll just be a quick bullet, and I’ll be dead.”

Matti is aware his parents want him to leave Iraq.

“They’ve seen what happens over here. People get beheaded, tortured, or have scud missiles shot at them. They don’t want their only son to face that, and I get it. That’s why I don’t try to defend myself or make them try to understand.”

Spreading ‘Detroit spirit’

Matti returns to Metro Detroit each summer to see his parents.

“I miss Detroit; how could I not miss it? I always say Detroit is my hometown, and Iraq is my homeland. My personality, the way I talk and think, is 100 percent Detroit.

“I miss watching the Pistons. I miss just driving around Dequindre Road for no reason. And I miss the trees we take for granted. There aren’t many trees in the Middle East. But I’m going to stay here and keep doing what I’m doing. I have a reason to live. I have a cause.”

Aside from emulating the shticks he learned from the disc jockeys he grew up listening to, Matti says he tries to bring what he calls “Detroit spirit” to the people of Iraq.

“People are in a dire situation here, and I tell them they should love being an underdog. That’s something people in Detroit know: You can still come out on top if you’re an underdog. If things are bad, they can get better. You just need to stay determined, and never give up hope.”

ghunter@detroitnews.com

(313) 222-2134

Helping Chaldeans

While radio is Noor Matti’s passion, he said he’s proudest of the Shlama Foundation, a nonprofit he created in 2014 to help Chaldean refugees.

“When ISIS took over Mosul in 2014, they displaced 120,000 people from their houses,” he said. “So almost every weekend, I do humanitarian work for the displaced Chaldeans. With the help of the Chaldean community in Detroit, we were able to raise $90,000.”

Donations go to food, medical supplies, education materials and school renovations, among other charities. The foundation posts videos and pictures online so donors can see people’s reactions when they receive the charitable gifts.

To donate, go to www.shlama.org.

http://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/macomb-county/2016/02/01/warren-dj-tweaks-isis-iraq/79674652/